The public library movement in the United States gained momentum in the last decades of the 19th century, encouraged by a combination of political, social, economic, and intellectual forces. The public library was heralded as an agency for general self-improvement, providing opportunities for education leading to an informed and therefore better electorate. The library was promoted as a continuing means of moral education that could prevent, or at least reduce, the social and moral problems associated with urbanization. Communities also had energetic leaders who recognized the need for a public library and were able to persuade their fellow citizens to vote in support of the new service.

Such boosterism and civic pride were characteristic of the Auburn Board of Trade which, in 1890, charged a committee to plan a library to serve Auburn residents and to “devise ways and means for its establishment.”

On October 27, 1890, the Auburn Public Library was officially chartered as “a working library, having the best books of reference, and the standard works of belles-lettres, poetry, philosophy, travel, and fiction; to cooperate with the schools; and to serve the entire community.” The Lewiston Journal’s report of that meeting was headlined: “Founded Well! The Auburn Public Library Gets a Start on the World, and a Happy One, Too. It Is Named, Organized, Officered, Endowed with By-Laws and Gets a Gift of $500 All in One Evening.”

Special lectures and programs were planned to raise funds to purchase books; the Journal reported on June 5, 1891, of such a lecture by Mrs. Alice Freeman Palmer. Sales of 600 tickets brought in $108.40. Other library support was raised by selling subscriptions and memberships: $25 entitled life membership in the association and eligibility to hold office; $15 plus $1 annual fee per year for the same privileges; or, $3 per family, $1 per individual for annual membership. The first major gift was $500 from Angela Smith Whitman in memory of her parents.

On July 22, 1891, Miss Annie Prescott of Auburn was appointed librarian and assumed her duties at a salary of $300 per year. The trustees rented two rooms in the Elm Block, above the Auburn Trust Co., for $375 per year (heated). The library opened for business on August 21, 1891, with 2,150 books and 30 newspapers and magazines. Response from the public was immediate and positive: in the first three months 383 subscribers were listed and circulation was 4,172. Miss Prescott also created from scratch, the library’s first catalog.

At first only one book could be borrowed at a time; then it was increased to two, only one of which could be fiction. Teachers could borrow three books at a time, “for schoolwork,” for seven days. Children could not get library cards until they were ten years old.

In 1895 the City of Auburn appropriated $1,000 for the library with the condition that the library be free to all Auburn citizens. As a result, 1,852 library cards were issued that year; there were 41,922 visits to the library; and 37,087 books were checked out. In 1898, the YMCA donated it’s own library of some 1,350 books to the APL.

“All of this extra work, including the corresponding multiplication of all the details has been accomplished by the librarian with very little outside assistance, although somewhat to the detriment to the most important part of the work, the careful attention to the wants of each person,” wrote Annie Prescott. Miss May Brown, a teacher, was hired for Saturday evenings at .15/hour and two grammar school boys were hired at .10/hour for weekday and Saturday afternoons and Saturday evenings.

The library outgrew the two rooms and in 1898 moved to the second floor of the Ora Davis House at the corner of Court St. and Mechanics Row, whose first floor contained the city offices. Miss Prescott reported, “As was expected, the greater convenience of the new rooms has contributed much to the better administration of the library, enabling the town’s people to come to us with increased assurance that their intellectual needs can be supplied.”

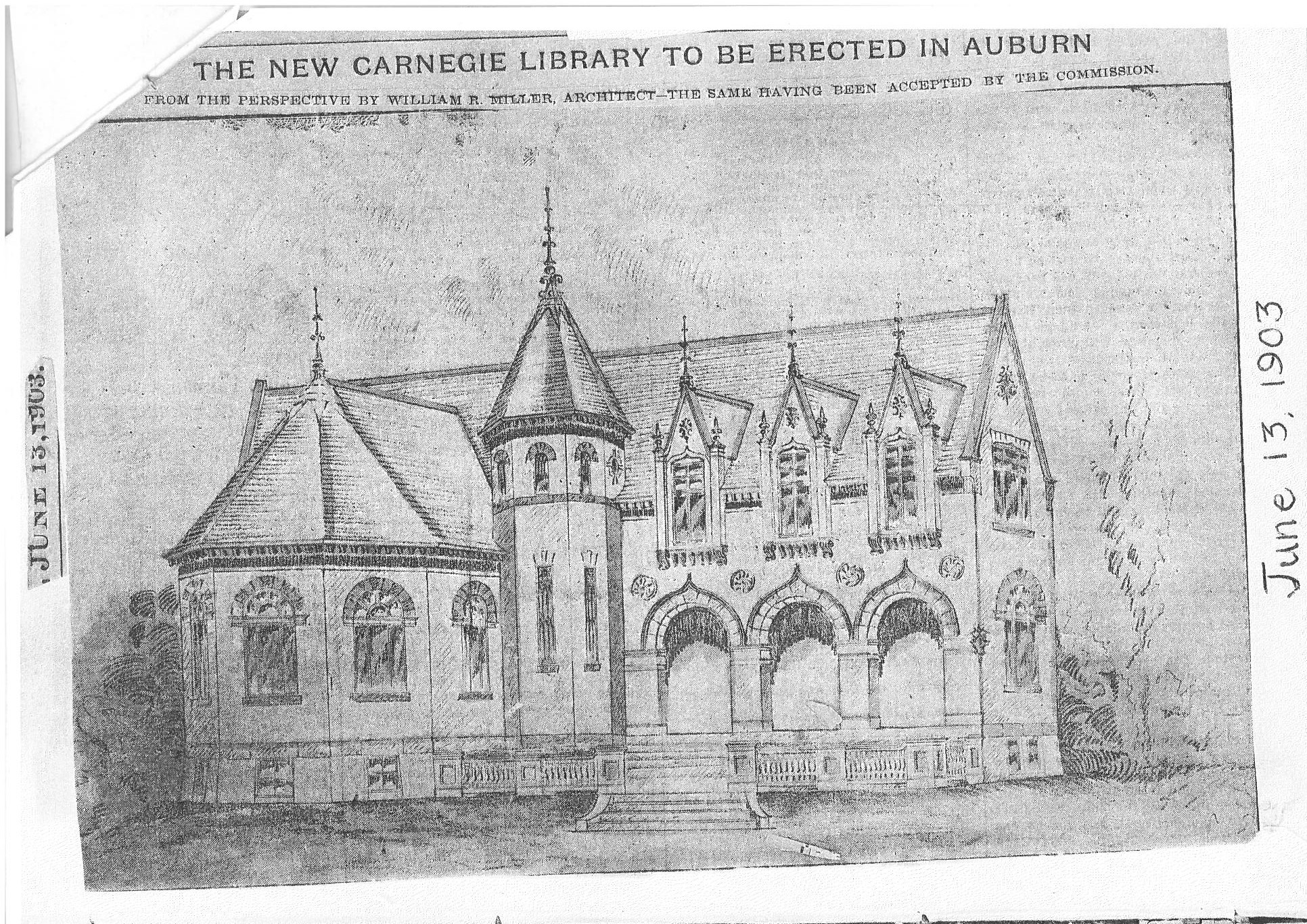

In 1902 library trustee George C. Wing received notice that philanthropist Andrew Carnegie would give Auburn $25,000 to build a library under the provisions of the Carnegie Corporation program through which $41 million was contributed to build 1700 libraries in the U.S. Carnegie had two requirements: that the municipality had to acquire the site and that an annual tax appropriation equal to 10% of his grant would be guaranteed. The Free Baptist Church was willing to sell its parsonage lot at Spring and Court Streets so the site was not a problem. The city’s annual appropriation to the library was $1,400, or $900 less than needed to meet Carnegie’s requirement.

The Journal reported a public meeting on the appropriation (1/26/1903). One person said, “We are already burdened with taxation…Such a library cannot be maintained for anywhere near the estimated figure of $2500….This would be a perpetual tax on our children.” Another rebutted, “It is the height of nonsense to refuse such a gift. It looks like a perpetual tax to some people, but isn’t it a perpetual tax to have roads, sidewalks, waterworks, street lights?”

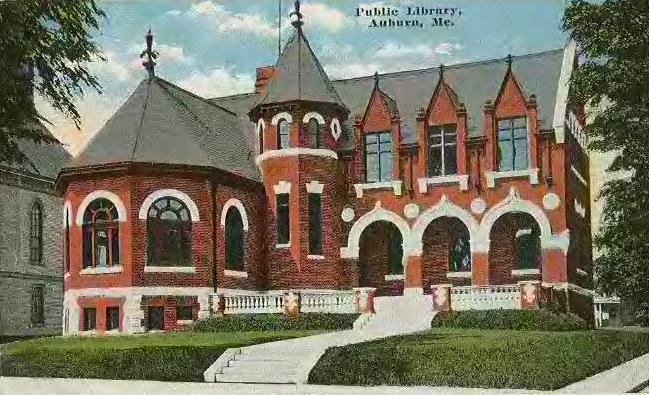

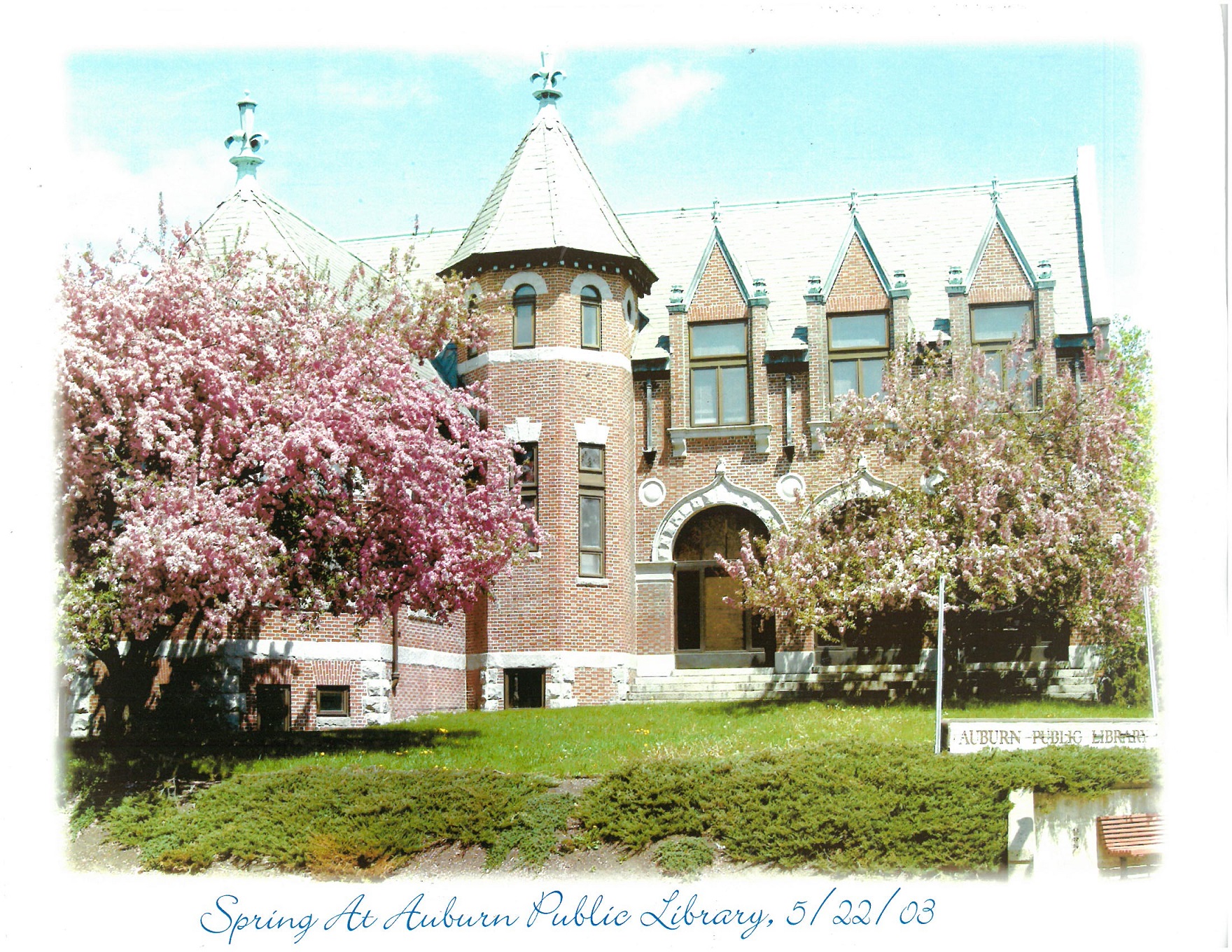

The Board of Aldermen unanimously voted to accept the Carnegie gift and to appropriate $2500. The parsonage lot was purchased for $6500. Ground was broken on July 22, 1903, and the new library opened in its new building on August 1, 1904.

The building was state-of-the-art as public library service was envisioned in 1904. It was designed to be a one-floor operation. “From the librarian’s desk a view can be had of the children’s room, the reading room, the reference room, and also the vestibule,” described the Journal. “This is intended to make the administration as economical as possible by enabling the librarian to see all parts of the building from one position.” The fireproof stack room would hold 40,000 volumes. The top floor had a room for the trustees and a lecture hall. Library hours were 10-8 Monday through Friday and 10-9 on Saturday; full-time employees worked 45-hour weeks.

“More people come, and they stay longer,” Miss Prescott reported. “We have provided for us a building which, for beauty and convenience, has scarcely ever been equaled for a like expenditure.”

In 1917 Miss Prescott resigned as librarian after 26 years. Georgiana Lunt, assistant librarian since 1913, was appointed head librarian, a post she held until 1954.

Despite the new building, or because of it, the library had to find more room. The children’s room was moved to the top floor lecture hall in 1920, eliminating the touted one-floor convenience. Electric lights replaced gas fixtures in 1915. The third level of stack shelving was installed in 1929. The coal furnace was converted to oil in 1947.

The library offered up-to-date services for the time. “From the first ours has been considered a progressive library for a small city and its methods and results are watched with interest,” Miss Prescott reported in 1908. Because school libraries were nonexistent APL offered rotating collections to all the district schools. “Every pupil in the three upper classes at the High School has received instruction by Miss Cornforth in the use of books here at the library….It is of great practical value. If it were not for this training in self help, the library force would not be large enough to wait upon the students, so many of them come” (1916).

Gail Whitehouse was the children’s librarian from 1921 to 1961. She was well known for her special Saturday morning story hours. She visited the Auburn city playgrounds in the summer to tell stories and encourage library use “to the children who had never taken books from the library.”

The library was sensitive to the political, social, and economic climate. It responded to the appeal for books for soldiers during World War I; it was closed for 29 days early in 1918 because of a coal shortage and for two weeks later in the year because of the influenza epidemic. In August, 1932, all salaries were reduced by 5% because of a city-wide salary reduction. Salaries were cut by another 5% in March, 1933. The 1931 levels were not restored until 1940.

The building was used to its maximum by the late 1940s. Miss Lunt put it, “As the librarian must be watchful for improved methods of administration and new services to be undertaken, so also must the building be kept adaptable to the purpose for which it exists,” pointing out that the stack space was inadequate and the 11 rooms were inconveniently arranged.

The long-awaited expansion came in 1956, when Amy Sherman was the head librarian. The 4,156 square-foot addition provided a new children’s room, three stack floors, and work space. The $85,000 cost was paid by the city.

Miss Sherman retired in 1973, after a career spanning 29 years at APL.

The new director, Fred von Lang, instituted a radical change: in July, 1974, the three floors of stacks were opened to allow the public access to the collection. For the first time in 70 years patrons could browse at will. The staff could devote their time and energies to helping people who needed assistance rather than retrieving books. Mr. von Lang also organized the library into departments with specific responsibilities–circulation, cataloging, children’s, reference, and administration. He expanded the telephone system from one phone at the main desk to five telephones with two lines. He also made preliminary plans to modernize the library.

This modernization came about in 1978 when Robert Dysinger was library director. A federal community development grant was made available to the library. The renovations created significant changes: the ground floor became the main entry, opening onto the lobby, circulation desk, and periodicals reading room. The reference room was redesigned and the children’s room relocated, both on the first floor. The top floor became library offices. An elevator connected the three floors. Truly, every one of the library’s 13,146 square feet became fully used.

In the late 1970s it was apparent that with the change to open stacks more specific classification numbers were needed. Errors occurring over the years in the cataloging system had not been corrected and computer-based cataloging required strict application of new standards. The Library of Congress Classification system was chosen over the Dewey system, used since the early 1900s. By 1990 85% of the collection was cataloged according to current standards and 55% of the catalog records were automated.

The Trustees adopted a new mission statement in 1982: “The Auburn Public Library exists to provide books and related materials that will assist the residents of the community in the pursuit of knowledge, information, education, research, and recreation in order to promote an enlightened citizenry and to enrich the quality of life.”

With a renewed emphasis on materials that were practical and useful, interesting and entertaining, library use increased dramatically through the 1980s. Circulation in 1980 was 123,265; in 1990, 242,519, nearly doubled.

The audiovisual collection began with a collection of donated long-playing records in the 1960s. Now the annual budget specifically provided funds to acquire cassette tapes, compact discs, and videocassettes. Recorded books for adults and book-and-tape “read-alongs” for children were among other nonbook formats adopted.

Children’s services progressed from the early days. Children were able to get library cards before they entered school. No longer were programs restricted to elementary graders; storytime participants were as young as 2-1/2 years old. The summer reading program, first held in 1953, acquired a “read to me” unit in addition to the section for older children. An important part of the children’s department was to work with parents and teachers to ensure that children develop information as well as reading skills.

Subject strengths established through years of careful collection maintenance included all aspects of art; music; and literature. The library’s genealogical and local history collection was among the better such in Maine public libraries.

The business reference collection was established in 1983. APL made a special effort to provide resources for small business and personal finance as well as career guidance.

Once again (as in 1898, 1954, and 1978), library services and collection outgrew our available space. In the fall of 1999, the Auburn Public Library’s Board of Trustees began planning a major capital campaign to raise funds to expand the facility but preserve the integrity and style of the original Carnegie-funded building. The Campaign Advisory Board included influential community figures such as former state legislator Barbara Trafton and Honorary Chairperson Senator Olympia Snowe. Told by a professional fundraising counsel that they could expect to raise $1.5 million, they surpassed expectations and raised over $3.5 million. The City of Auburn approved a bond issue for an additional $3.5 million, and the newly-expanded building opened its doors in June of 2006, followed by a grand opening celebration in September 2006.

The 33,000 square foot facility features public computers, a 13-station computer lab, a three-station media lab, private study rooms, a children’s program room, and two public meeting rooms. The grandeur of the original building is preserved in its Grand Reading Room and Local History Room, while its wireless access throughout the building makes it 21st century capable.

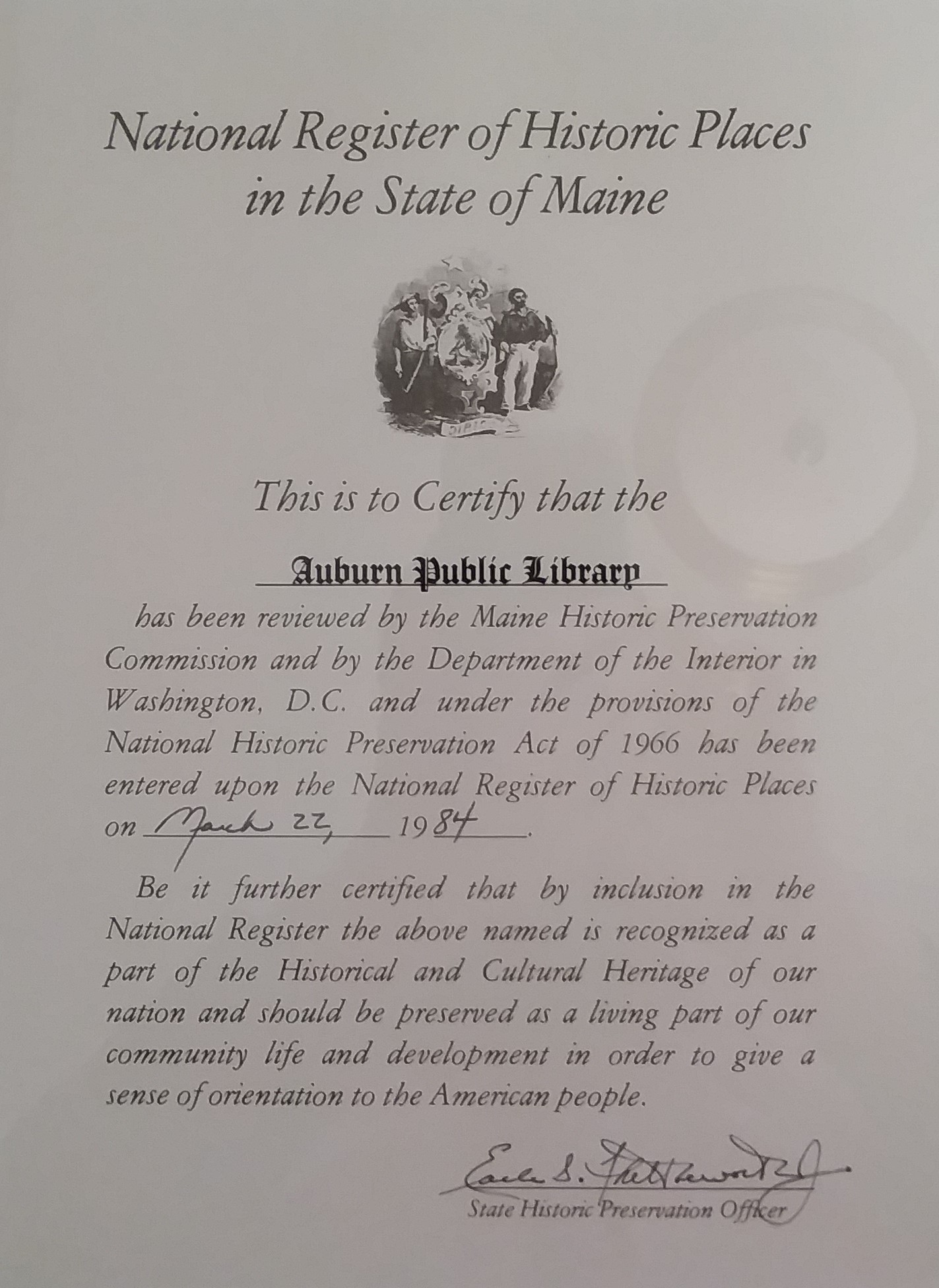

Its faithfulness to the original architecture, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, won it an award from the Maine Historic Preservation Commission in 2007. Artwork graces every room, and high windows let in the sunlight. A special mural near the Spring Street entrance honors the families and businesses that funded the building, and its flexible open floor plan helps ensure that the Auburn Public Library will continue to meet the needs of its community.

In 2011, a significant improvement was made to the building when a $20,000 grant from Proctor & Gamble’s Greater Cincinnati Foundation enabled the creation of an enclosed Teen Space on the second floor. A second P&G grant made possible the creation of another new space on the second floor to house a digital media lab targeted to teens. These two improvements, coupled with a designated teen librarian and many teen-oriented programs have resulted in steadily growing use of the library by youth ages 12-18.

The media lab illustrates a continuing trajectory of change as the library adjusts to the impact of technology. Use of APL’s internet computers has dropped as more and more people use its wireless on their own devices. The library has added e-books and e-book devices to its circulating collection. Uncertainties surrounding digital rights management threaten the ability of public libraries to loan the content they have traditionally provided, and libraries including APL are responding by increasing emphasis on their roles as community centers and catalysts for content creation.

Whatever challenges the future may bring, APL will continue to identify ways in which the library can engage, enlighten and enrich the community.

Librarians

Annie Prescott (1890 to 1917)

Georgiana Lunt (1917 to 1954)

Amy G. Sherman (1954 to 1973)

Library Directors

Frederick Von Lang (1973 to 1977)

Robert Dysinger (1977 to 1981)

Nann Blaine Hilyard (1982 to 1993)

Charles E. Howell (1994 to 1996)

Steve Norman (1997 to 2001)

Rosemary Waltos (2001 to 2008)

Lynn Lockwood (2009 to 2013)

Mamie Anthoine Ney (2013 to 2023)

Donna Wallace (2024-present)